In Riley County, 17,449 people are affected by drought conditions, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System. The Ogallala Aquifer is projected to be 70% depleted in 50 years because of an increase in drought in Kansas since 2020, according to the American Bar Association. These are tangible impacts of Kansas’ current drought conditions.

The National Drought Mitigation Center defines drought as “a deficiency of precipitation over an extended period of time (usually a season or more), resulting in a water shortage.”

Andrew Terhune, environmental compliance and regulatory specialist supervisor for the Kansas Division of Water Resources, said the “majority” of Kansas is abnormally dry to moderately dry.

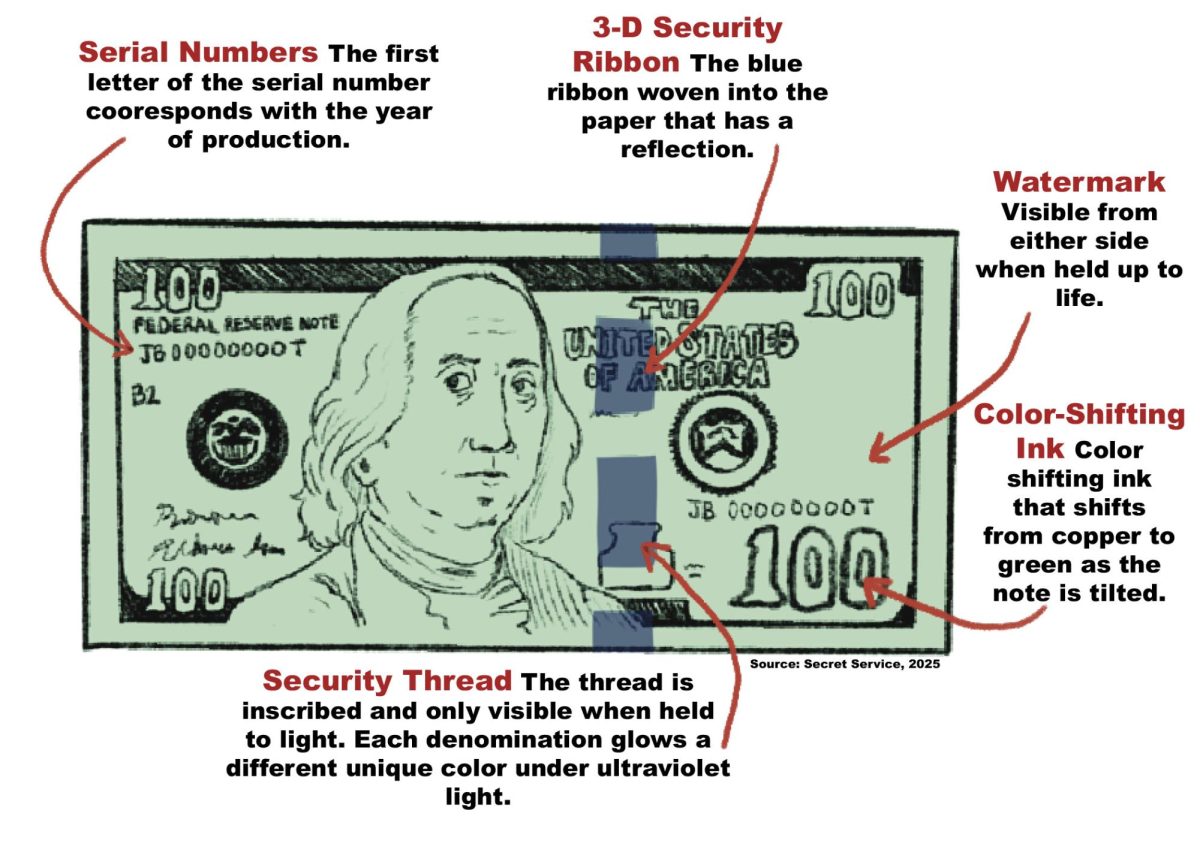

The U.S. Drought Monitor classifies drought into five categories:

D0 – Abnormally Dry

D1 – Moderate Drought

D2 – Severe Drought

D3 – Extreme Drought

D4 – Exceptional Drought

According to the NIDIS, “The Drought Severity and Coverage Index [DSCI] is an experimental method for converting drought levels from the U.S. Drought Monitor map to a single value for an area. DSCI values are part of the U.S. Drought Monitor data tables. Possible values of the DSCI are from 0 to 500. Zero means that none of the area is abnormally dry or in drought, and 500 means that all of the area is in D4, exceptional drought.”

Terhune said drought causes significant strain on farmers, putting stress on agricultural business, whether it’s livestock or irrigating crops. Farmers with domestic water sources find themselves running out of water.

“Folks that are using … ponds or shallow wells, or creeks and rivers, if we are in drought conditions, if they’re in moderate to extreme or severe drought, then the surface water is probably not going to be available,” Terhune said. “They’re going to be … using the groundwater.”

Nate Bjerke-Harvey, co-owner of Piccalilli Farm alongside his wife Alison, grows an assortment of crops, calling himself a “farmer’s market farm.” He said the drought in Kansas directly affects his business.

“Well, we irrigate our crops, and we pay for our irrigated water,” Bjerke-Harvey said. “So, the primary implication for us in terms of impact on the vegetable end of our business has just been an increased cost for production with less rainfall.”

In the last four years, Kansas drought conditions peaked in November of 2022 with a DSCI of 369. These conditions affect more than the land; Bjerke-Harvey said they affect livestock as well.

“The other piece of it is we operate a pasture-based management system for our poultry and our goats,” Bjerke-Harvey said. “So, we manage a flock of about 300 laying hens and we do somewhere around 500 meat birds a year and turkeys and all that stuff. [The] lack of water has just meant less vigorous pasture growth for us. So, our rotation pattern is a lot faster than it had been previously just because we’re exhausting pasture. Our animals are exhausting the available nutrients in pasture a lot faster. So, it requires quicker rotation and more intense management.”

Katie Goff, geographic information systems coordinator at the Kansas Water Office, said the office created the Kansas Water Plan to mitigate drought effects.

“The Kansas Water Plan is the overarching, comprehensive plan to address current water resources and then planning for future needs,” Goff said. “So, we break it down into five guiding principles, so five topics, and each one goes more in-depth of how to plan for those topics into the future.”

According to the Kansas Water Plan, the five guiding principles are to “Conserve and Extend the High Plains Aquifer,” “Secure, Protect and Restore our Kansas Reservoirs,” “Improve the State’s Water Quality,” “Reduce our Vulnerability to Extreme Events” and “Increase Awareness of Kansas Water Resources.”

Bjerke-Harvey said on his farm, they’ve adapted to produce high yields of crops even in dry conditions.

“We started with a dense clay loam in terms of soil variety that was in our vegetable production acreage,” Bjerke-Harvey said. “But we’ve been using the same soil for about 10 years and through that intensive fertility management, we’ve gone from something that was not very fertile and didn’t drain very well to something that has pretty great drainage and really high fertility. So the soil is not only a little more resilient to high rain events, it’s able to hold the water better. But the flip side of that is during drought situations, it holds the limited irrigated water that we apply to it better.”

Terhune said there are some policies enforced by the Department of Agriculture to help Kansas conserve water. Many surface water areas are covered under Minimum Desirable Streamflow.

“So, they’re kind of set up with those permits the water-users have to where if there’s a water shortage or the water table, in this case, the cricks, rivers or streams that fall under MDS, fall below a certain flow, then our agency sends out orders to shut those folks off so that they can’t pump anymore.”

Terhune said it is difficult to employ MDS in western Kansas, where water sources are primarily wells from aquifers.

“They [KS Division of Water Resources] have allowed multi-year allocation tools, because they learned in a drought of 2011-2012 that if they didn’t have something that allowed them [farmers] to pump over their authorized quantity, that all the crops would burn up,” Terhune said. “… So now folks that are finding themselves in bad spots can utilize a Multi-Year Flex Account, is what it’s called, to balance out their authorized quantity over multiple years.”

Goff said even though drought primarily affects agriculture, it’s an issue all Kansans should consider.

“A lot of our economy is from agriculture,” Goff said. “Every little bit in our cities makes a difference.”