Editor’s Note: Zoe Schumacher has found a kidney donor. Read about it here.

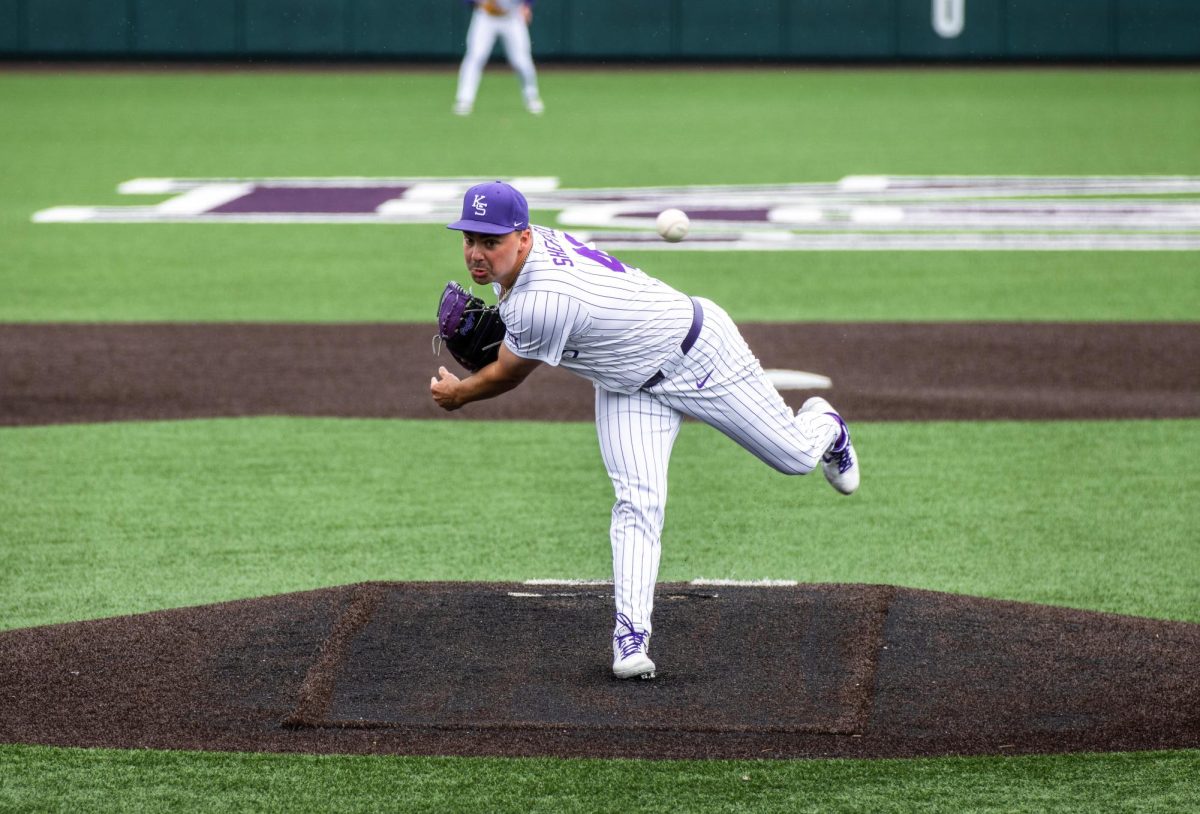

Zoe Schumacher fell in love with Kansas State as a child, experiencing firsthand the vibrance of K-State’s traditions alongside her family, sparking her love for marching and pep band. When it came time for her to choose a college, she chose K-State to major in marketing and graphic design. Through making her childhood dreams come true and joining the K-State marching band, Schumacher found that and more.

Schumacher and one of her roommates, Erin Flax, senior in music education, met through the band. At the end of the spring 2024 semester, they looked forward to playing in the band for the fall football season and cracking jokes about being too old to go out in their “senior” age, when Schumacher’s busy student life took an abrupt turn.

“I started getting really sick, often, like having a cold, but worse, and I was super fatigued, and just thought that I was pushing myself too hard,” Schumacher said. “I was at class, and I started getting very strong, acute pain in my abdomen, and I had been throwing up the day before, so I was not sure what was going on … I thought I might have appendicitis.”

Schumacher said as the pain became more sharp, she realized this was more than just a cramp and called Flax, asking if she could take her to the emergency room.

“[Flax] just dropped everything and took me to the ER, we were … joking to make me feel better while I was going through the pain, and then while I was also scared, not knowing what was going on,” Schumacher said. “And she stayed until my parents were able to come from Wichita.”

Schumacher was diagnosed with End Stage Renal Disease, a final stage in kidney disease where kidneys permanently lose the ability to fully remove waste and balance fluids. At the time she was admitted to the hospital, Schumacher’s kidneys were functioning at 20%.

“I remember that there was a point where she had to get her blood drawn, and she does not like needles, they really stress her out,” Flax said. “So I had to hold her hand, and I was trying to make her laugh while that was happening.”

Flax said the severity of the situation set in for her when she realized Schumacher would be staying in the hospital overnight, and driving back without her friend was one of the hardest parts of the day.

“One day, she was fine, and then the next, her entire life changed; she kind of went to the hospital one day and then never came back,” Flax said. “The apartment did not feel the same without her … there was definitely a hole there.”

ESRD requires the patient to either regularly go through dialysis, which removes the toxins in place of the kidney, or receive a kidney transplant.

According to the National Kidney Association, more than 101,000 Americans are on the waiting list for a live kidney transplant, but only 17,000 Americans receive one every year.

While Schumacher was put on a waitlist for a transplant, it’s uncertain of how long it’ll be before she finds a donor, so she’s been going through dialysis.

“I would go [to a clinic] four days a week, and for three hours each time, and just be sitting on a chair with blood getting taken out of my body, filtered, put back into my body … my life was not the same at all, because I couldn’t do classes at the time,” Schumacher said.

To return to classes, Schumacher underwent surgery so she could do peritoneal dialysis, a form of dialysis that can be performed at home.

“I have a machine that I have to set up every night, and it takes solution, and it puts the solution into my body and into the peritoneal cavity in your body, which is surrounding your organs, and then that solution extracts the toxins, and then the machine also pulls the solution back out after a little while, so it does your kidney function for you basically every night,” Schumacher said. “Even though I’ve experienced some physical trauma from the medicine and everything, I feel so much better than before I got my diagnosis, because, you know, nothing was being done to help me.”

While dialysis helped Schumacher go back to school for her senior year at K-State, it’s only a temporary solution until she can find a donor.

Ideally, Schumacher’s donor should be student-aged, so she’s looking to the K-State family for a donor.

“I don’t have a large family, so it’s difficult to find a match — I don’t have a bunch of siblings,” Schumacher said. “My parents are not compatible with me … I don’t have a large family to get tested for kidney donation. So I have been reaching out to my K-State family, particularly my band family.”

Flax said she feels helpless seeing Schumacher’s struggle, and is in awe of her friend’s ability to move forward.

“She’s the kindest, most generous person I know; she’s always putting others before herself and is just a really great all-around person to have,” Flax said. “It’s definitely been hard to watch someone who’s so close to me going through something so difficult … and she’s honestly really inspiring to watch go through this, because she just takes it day by day … but it’s definitely still hard, because I want to fix it for her, and that’s not something I can do.”

Tim Schumacher, Zoe’s dad and K-State alumnus, isn’t able to donate to his daughter, but he is interested in a kidney paired donation through the National Donor Exchange Program.

“I would donate my kidney even if it wasn’t going to Zoe, just because of what I’ve had to see her go through … but I want to make sure that she gets one first,” Tim Schumacher said. “[A kidney paired donation] complicates the whole process … instead of only needing one compatible party … there would be four people involved … so we would need someone with a donor compatible with Zoe, who I would also be compatible with.”

Tim Schumacher said he’s inspired by Zoe’s resilience through her diagnosis.

“Obviously, my wife and I would never wish for her to be home with us [before Zoe could return to classes], but even during the hardest parts we found joy,” Tim Schumacher said. “It’s all made me thankful for life.”

Flax said there is no commitment when starting the donor-testing process.

“You can always, you know, back out at any time,” Flax said. “If you’re interested at all, go for it, or at least do a little bit more research, see what it might be like for you … it would be going to truly, a really great cause and a really great person.”

Since Schumacher has an A+ blood type, a compatible donor would have A+, A-, O+ or O- blood. Donations can also be scheduled if anyone is interested in being a donor but wants to wait for a school break.

Those interested in beginning the testing process for donor compatibility can contact Zoe’s KU Med Living Donor Nurse at 913-588-0266.