We live in an age of uncertainty. The aftermath of war, disease, political polarization and economic instability has invoked a nationalistic longing to return to a rose-colored past, but the uncertainty is not unfamiliar.

The similarities between the present United States and those of early twentieth century fascist regimes are not prophecies, but they are definitely red flags.

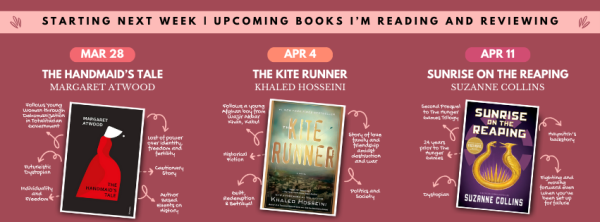

It’s not a coincidence, then, that according to AP News, sales for the dystopian speculative fiction, “The Handmaid’s Tale,” by Margaret Atwood, spiked both times Donald Trump was elected president.

Its authoritarian regime and misogynistic society are unsettling, yet familiar. It’s not a mirror, or a prophecy, but a speculation that often feels a little too close to home.

Margaret Atwood made one rule for herself when writing this story: everything that happens in the book must have happened at some point in human history.

It’s telling us what could happen, because it did happen.

It follows Offred, a formerly American woman forced to submit to the Christian fundamentalist regime that overtook the United States government. The new country, The Republic of Gilead, prioritizes very literal, Christian values to justify its oppressive agenda, including genocide, state-engineered rape and mass dehumanization.

Society in Gilead has oppressive rules against political, intellectual and sexual freedom.

Women’s entire identities are remodeled to shape their function to men. They are not allowed to read or go out by themselves, and women known as Handmaids are used by upper class men to bear more children. Offred, a Handmaid, describes herself at one point as “a two-legged womb for increasing Gilead’s waning population.”

Offred’s real name is intentionally never mentioned in the story. It’s a combination of “Of Fred,” preventing even her own identity from escaping who she belongs to. The name also, as Atwood states in her author’s note, plays as another form of Offred being offered, as the words are very similar.

There’s a terrifying familiarity to the story: sexist and crude language from politicians against women, a reduction of women’s autonomy, the erasure of people beyond straight white men from the public eye, the separation of families at borders, the rise of Christian nationalism, and more. It’s a speculation regarding things we’re experiencing today, crafted by what’s already happened before, and it isn’t pretty.

We are not living in a replica of the past, nor was Atwood trying to create one, but Gilead’s history is our history, and our systemic failings are growing scarily similar to those in the novel.

Atwood wrote this story in response to conservative opposition to the second-wave feminist movement, which pushed for more legal rights for women. The movement also faced a lot of internal fighting based on fundamental disagreements between different opinions about the sex trade, which I found similarities to at different points in the book.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” asks what the U.S. would look like if the anti-feminist opposition prevailed, but more importantly, who would benefit from it?

Fun fact: it wasn’t middle-class women.

In terms of prose, Atwood has a poetic, long-winded voice, full of keen observation.

The layering of her sentences was intentional and often read like poetry in sentence-form, but I will admit that I had a difficult time wrapping up some of the sentences while remembering where we started. I’m not knocking off any points for that, because it had its value, it just was a hurdle I wanted to disclose.

I’d also like to clarify that this book is not anti-Christian, it’s anti-fascism, demonstrating a scenario where face-value religious texts can be manipulated into justification for dehumanization. Even the people highest on the political hierarchy didn’t fully believe everything they preached, often going against their own words when it benefited them.

Overall, I’d rate this book five stars. It’s not the story of a hero who will save the day, but a woman who is trying to survive. It’s not always a pretty read, but it is full of hope, even in its worst forms. More importantly, I think it’s still a bestseller because there is hope within readers, that we can unify against all these darker sides of history to fight not only for feminism, but also against fascism, nationalism and dehumanization.