The power of water entranced Dr. Prathap Parameswaran. It perplexed him. Growing up in southwest India, he often saw a pattern: after the rain, intense, crippling drought followed three months later.

“I began to wonder, why can’t we do this better?” Parameswaran, associate professor of civil engineering at Kansas State, said.

The average rainfall in southwest India can reach about 80 inches, according to Climates to Travel. In 2024, Kansas had an average rainfall of 33.38. As of Oct. 21, Riley County had a drought intensity of D0, abnormally dry.

Month by month, Kansas faces drought, affecting not only residents but also farmers who raise crops and livestock. These conditions and Parameswaran’s observations led the associate professor to work with a team of researchers at K-State and across the region, and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Oklahoma State University and Seward County Community College to develop a circular waste-recovery system.

Parameswaran said that he’s always been interested in improving and preserving the environment.

“As a trained engineer and a general human being, I have always desired to make the environment better,” Parameswaran said. “Through my work in the paper industry early in my career, I was introduced to the idea of reducing and reusing. … This has informed my view of wastewater that differs from others; that wastewater is simply a misplaced resource.”

Susan Metzger, director of the Kansas Water Institute, said this project started in partnership with Fort Riley and the Department of Defense.

“Initially, the technology’s concept was to treat wastewater at a major military installation and then have that water supply still available for the residents of the installation,” Metzger said. “When that grant opportunity ended, we still had the technology that we were developing, so we moved that technology to our swine operation here north of campus and have continued to perfect it over the years. Now we are ready to move the unit currently at the swine operation to our dairy operation and then hopefully also to some larger dairies in western Kansas.”

The water will “ideally” be used as drinking water for livestock and will allow farmers to “maximize the use of that water throughout the calendar year.” Metzger said the goal isn’t to make drinking water for humans, but for animals and crops.

“They take water out of a lagoon, which is the dirtiest water you can find on a feed yard, and send it through a series of membranes and technologies such as reverse osmosis, then the outcome is a separation of solids,” Metzger said. “So everything that was gross in the water before is now separated in solids that can be used for fertilizer. The goal is to make it as clean as what you would want to feed back to your cattle.”

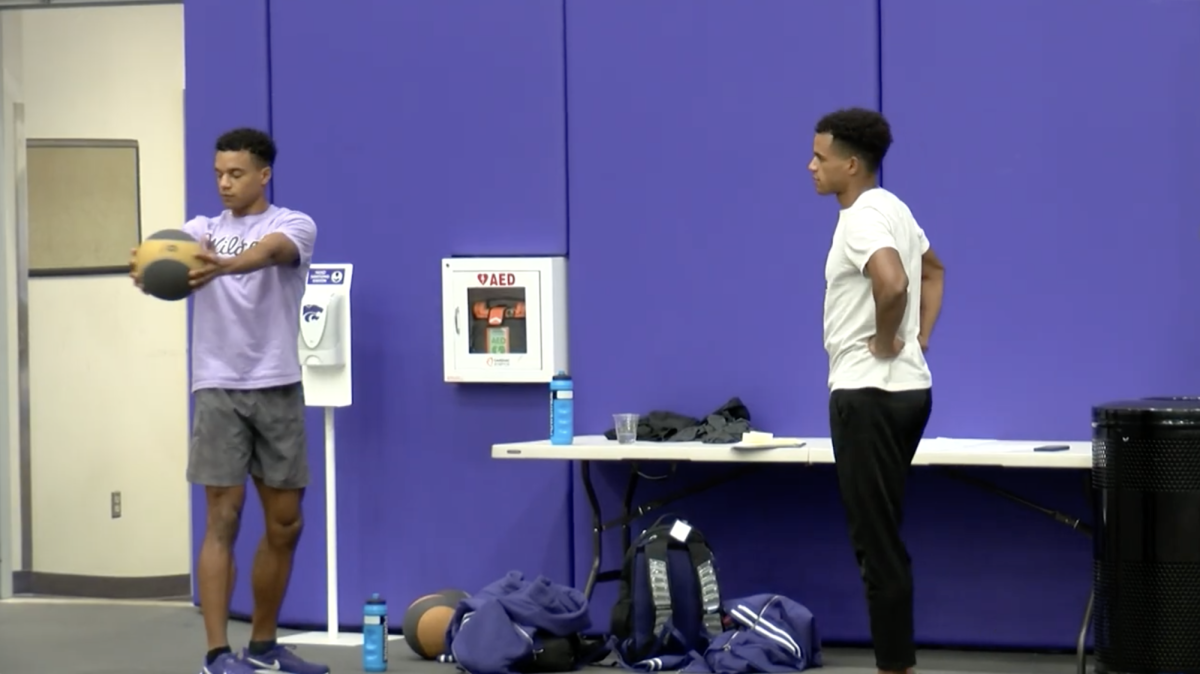

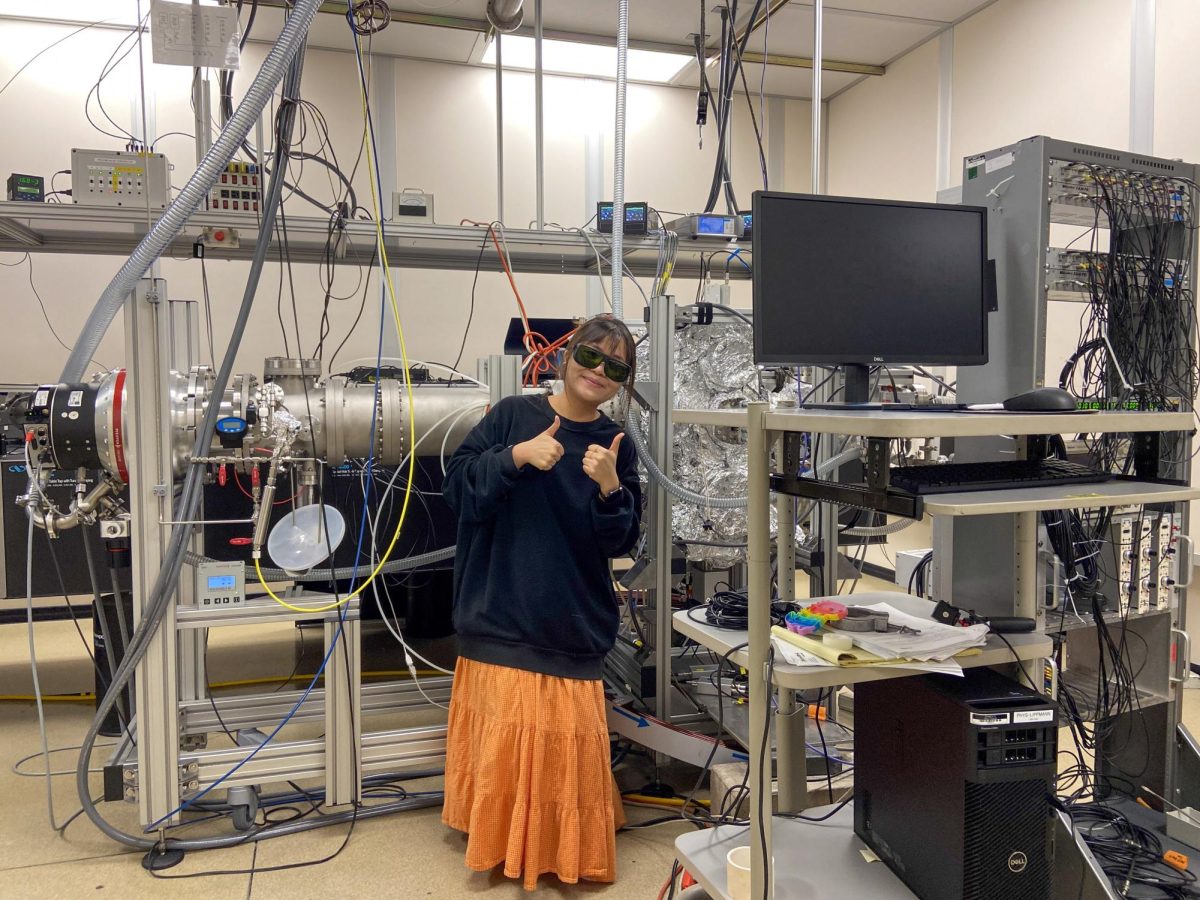

This study is conducted in conjunction with K-State researchers, graduate and undergraduate students in the College of Engineering.

“… [The students] have helped develop the technology over the years and continue to help develop the technology going into the future,” Metzger said.

Parameswaran said that what is filtered out should also be usable.

“The three byproducts, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus, can be applied to fields and used as inorganic fertilizer and can be applied to other spaces,” Parameswaran said.

This technology, which Metzger said can sound “gross and futuristic,” has already infiltrated day-to-day society and can be “applied for human consumption.”

“In the City of Wichita Falls in Texas, they have pioneered the technology that they call toilet to tap, where you take human wastewater in a large city and you treat it to the point where that water is clean enough for you to turn on your kitchen sink and to drink that same water again and again and again,” Metzger said. “The City of Wichita here in Kansas is now embarking on that technology for the entire city of Wichita and helping to shape our policy to make that possible for the entire state.”

Parameswaran said that this research aims to make this science more accessible and affordable.

“This knowledge has been available for three or four decades, but it is expensive to put into practice, so not many organizations or operations have really tried to implement it yet,” Parameswaran said. “We are exploring different ways to decrease the cost impact so that this can emerge as a realistic solution to help preserve the [Ogallala] aquifer.”

Jas Dale, an irrigation expert with Western Kansas Irrigation, works with Parameswaran to “come up with a quality of water that the cattle could drink.”

“We did a demonstration last Dec. 3 in Garden City with wastewater from a Fairleigh Feed Yard with technology that we took lagoon water to clear drinking water, and also we worked with KLA to help,” Dale said. “They were the third-party testing, but with K-State’s help, with Susan’s help, Kansas Water Institute and Prathap, because he was out at the meeting, we’re collaborating together to come up with a scalable system to go into a feed yard to do this on a large scale.”

Through his work with feed yards across Western Kansas, Dale often works with K-State entities.

“We can come up with the technology to clean, reclimate the wastewater into something drinkable, but we have to know what the parameters are, and this is where the collaboration with Prathap and K-State is coming,” he said. “This is the help we’re getting from them.”

The goal of using multiple teams to preserve the Ogallalla Aquifer is to leverage each team member’s strength to have more impact sooner, Parameswaran said.

“We have experts at UNL chemical engineering and material scientists that are … tweaking the membrane properties to make them even more impactful,” he said. “Oklahoma State already has advanced water reuse concepts in place, so that’s where they come in. We know that the majority of the problem occurs in Southwest Kansas, in Seward and Finney counties and around Dodge City and Garden City, so we were looking for a partner to join the team to help disseminate the information to that region of the state; Seward County Community College provides the people, students and workforce to help us get this information out in that area.”

Dale anticipates the program will officially start in late 2026.

“It’s a pilot program, and the pilot program is our wetland trailer that we could move around to different venues,” Dale said. “But we have proven the theory of taking wastewater to clean drinking water.”