Dr. Wayne Goins

Dr. Wayne Goins’ story began with homemade “guitars” crafted from cardboard, plastic or anything else he could get his hands on while growing up in Chicago’s South Side.

“I have been obsessed with guitar since the day I was born, and all I ever cared about playing was guitar,” Goins, director of jazz studies at Kansas State, said. “… Every Christmas all I wanted was a toy guitar. I would get plastic guitars and all of that, and then my father finally brought a real guitar home when I was about 10 years old. I was playing it in my head before I even had a real guitar.”

Goins traced his love for guitar back to living-room performances on a golden orange guitar. The rich sound of blues music echoed through their family home.

“I had an uncle,” he said. “His name was Jimmy Jones, and he was a great blues guitar player. Maybe about once or twice a year he would come over to our house and bring his Fender amplifier and Fender Jaguar guitar. I remember this guitar was beautiful, and he would just set up in our living room and just play.”

Goins’ uncle got him his first professional gig at just 12 years old.

“I made $70,” he said. “This was like 1972 or 1973, and I played for my mother’s birthday. One of the songs I remember us playing was ‘Love and Happiness’ by Al Green.”

Today, more than five decades later, Goins still finds joy through music, teaching jazz classes at K-State, including the Concert Jazz Ensemble and smaller group combos.

“[The combos are] the Swing Machine, which is our top-level combo; the intermediate level, which is House Records; [and] the beginner level, which is called Combo Nation.”

Goins teaches Jazz Improvisation and Jazz Theory while co-teaching Protest Music. He also offers private guitar and jazz lessons.

Though Goins found a passion for guitar in his early childhood, it wasn’t until his high school years that he discovered his love for jazz while working a summer job at Paul Robeson High School.

“They had a jazz band, a big band, like a 17-piece group, and I had never seen that before because our school didn’t have it,” he said. “… I fell in love with that and I wanted to be in it. It was like watching a big machine, and I wanted to be inside the machine. I begged that band director to let me in, and he did.”

Goins turned that experience into a deep love for jazz, impressed with the powerful sound and possibilities of large-band music.

“Jazz is the only American art form,” he said. “For that reason alone, it is worth us preserving, and nurturing, and growing and sharing with the whole world, because it is the one thing that’s ours.”

Goins instills the value of jazz into his music students, teaching from many sources — including a book he authored himself.

“My jazz improvisation book is called ‘The Wise Improviser,’” he said. “This is the book that I teach here to teach my jazz students how to improvise.”

Goins’ other publications include “Emotional Response to Music: Pat Metheney’s Secret Story,” “The Jazz Band Director’s Handbook: A Guide for Success,” “A Biography of Charlie Christian: Jazz Guitar’s King of Swing” and “Blues All Day Long: The Jimmy Rogers Story.” He has two biographies in the works and owns an independent record label, Little Apple Records, where he releases his own music.

Goins also prioritizes teaching through real-world experience, taking students to Bluestem Bistro to perform every Sunday from 10 a.m. to noon.

“It’s been sort of a feeding ground, so to speak, for students who are interested in jazz and actually want to get some real-life experience performing in front of people, and it’s been incredibly successful,” Goins said. “… It’s been generation after generation of jazz students who’ve been able to take advantage of that, make some money and just develop and grow.”

Since coming to Manhattan in 1998, Goins felt appreciation from the K-State family. Though his roots are in Chicago and he’s experienced the music scenes of Atlanta, Boston and more, he plans to call The Little Apple home for many more years.

“I love this place so much,” Goins said. “It’s the people, it’s the culture, it’s the atmosphere, it’s the warmth. I just feel like I’ve been embraced by this place from the time I got here. … Even though it’s [a smaller city], our ideas are just as big and are just as important as anybody else’s in the rest of the world. … You don’t have to be in New York to have New York attitude.”

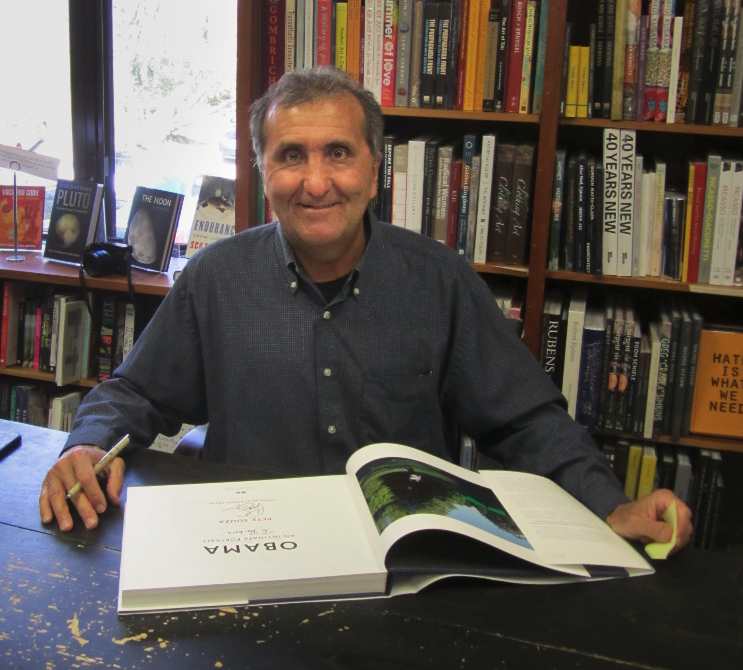

Jason Scuilla

Jason Scuilla teaches the printmaking courses at Kansas State, a medium he said requires physical discipline.

“There’s now quicker and more efficient ways to do things, but that doesn’t make them better,” Scuilla said. “… There’s something about it [printmaking], that human touch and that human craftsmanship — it transfers through that object.”

Scuilla developed a love for printmaking when earning his undergraduate degree at University of Central Florida, where he was an undecided major. It wasn’t until a trip to Italy that he decided to pursue a career in the field.

“Based on the work I had made in undergrad, I got a scholarship to attend Temple University, the Tyler School of Art,” Scuilla said. “Part of that, I got sent to Rome, Italy to work in their print shops for an entire year, which was transformative for me.”

The first time Scuilla felt true emotions invoked by visual art, he said, was during his apprenticeship in Rome.

“Growing up, I could be moved by music and moved by movies, and I could watch a movie and feel real emotion, maybe sadness, or sight or passion,” Scuilla said. “I could hear a song and be affected, get chills and be affected physically and emotionally. Going to Italy was the first time that I got to experience visual art, fine art, that could affect you that way, and I didn’t really understand that it could until I saw it.”

Scuilla’s time in Italy also taught him to find the connection that threads art together from generation to generation across different mediums and time periods.

“The biggest revelation wasn’t just that I was moved by that art, but I could look at an early medieval woodcut, or I could look at a classical Roman sculpture or I could look at a Byzantine mosaic,” he said. “These things are hugely different in what they are in their process. Some look crude, some look refined, all this stuff, but you start to realize that there’s this thread through them, this timeless ability to move people. It makes you question, how is that happening? … That’s something I try to accomplish in my own work and something that I work with the students on, to try to find their vision in a way that they can move people, too.”

When Scuilla arrived at K-State, opportunities for aspiring printmakers were slim. He developed the program with the help of passionate students who loved the collaborative and community-based nature of printmaking.

“The students we attract are students that come from all over the university,” Scuilla said. “Even if they’re in another major, the print shop feels like a home to a lot of our students.”

Printmaking allows artists to create multiple “originals” of the same piece, aiding the community and social aspect of the medium.

“In printmaking, once you spend all that time making something, you can print it in an addition so that you can trade with friends or sell prints, but not jeopardize having an original for their portfolios,” Scuilla said.

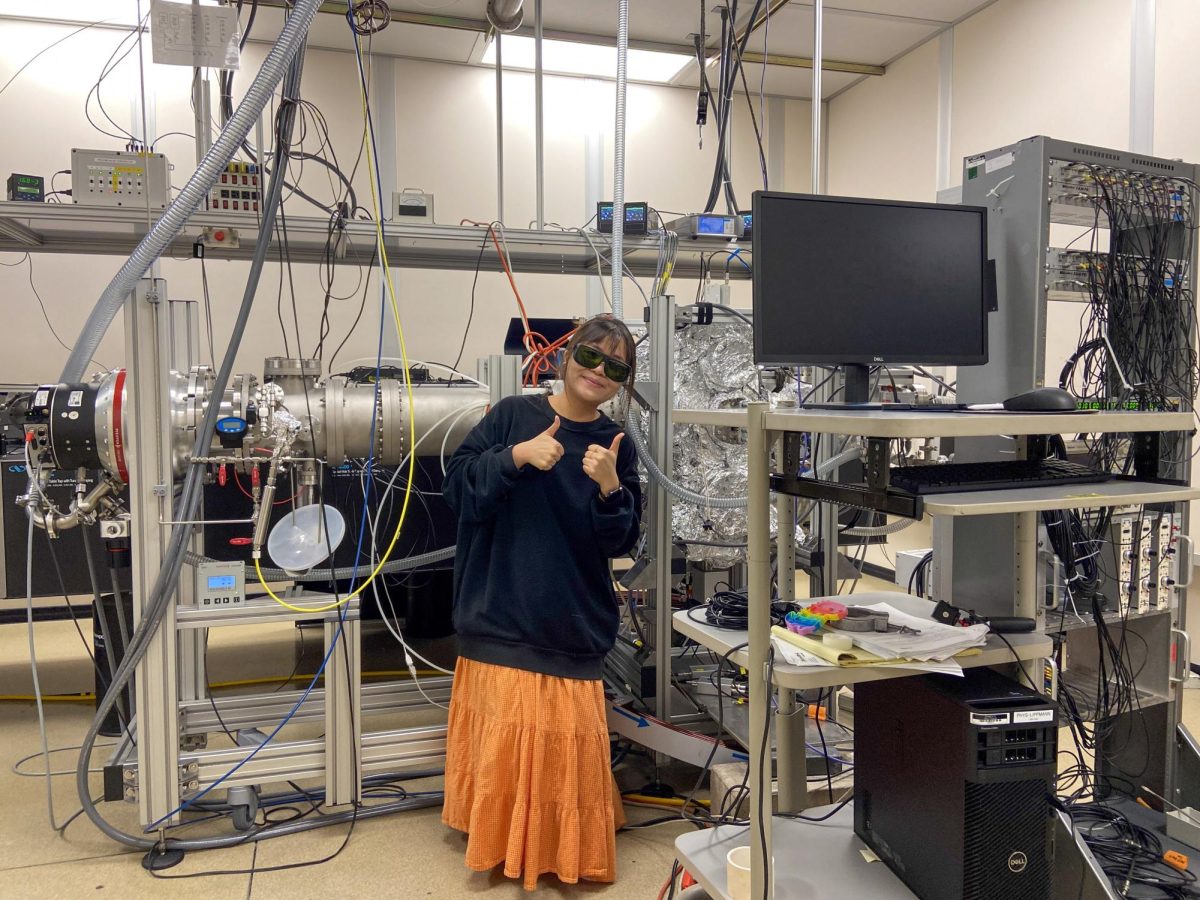

Today, over 15 years after Scuilla arrived at K-State, the university’s printmaking facilities are state-of-the-art.

“We are an internationally recognized shop for a few different things,” he said. “One, of course, for quality of our student work and our faculty, but we’re also known for our focus on safe and new technology. Last year we hosted the 2024 Mid-America Print Conference. People came from all over the country to K-State to see what we do, see our shops, demonstrations and workshops.”

The printmaking department at K-State places an emphasis on curbing dangers artists are exposed to.

“One process that we’re most known for, instead of etching with traditional acids, we use a low-voltage electro-chemical reaction that we’ve perfected here over a decade, and we’ve become known for that,” Scuilla said. “The other thing we do is create safer solvents with no VOCs. We use vegetable oil-based solvents that we develop here at K-State.”

The processes created at K-State, Scuilla said, are used not only by students of the university, but by professionals, as well.

Throughout his years of field experience, personal projects and classroom expertise, Scuilla said one thing keeps him at K-State:

“It’s the students that we have here,” he said. “… These are students that come from unique backgrounds out here, and they have something unique to say. Part of what’s exciting is to help them find that voice and express something that I think needs to be said.”

Currently, Scuilla is working on his series “Proxy War Monuments,” which he started during COVID. Inspired by “The Disasters of War” by Francisco Goya, Scuilla aims to capture the psychological warfare individuals feel in today’s digital age.

“In my own mind, when I’m working on these, I just think of all the stuff filtering through my head and think of it as creating these sort-of monuments of these psychological battlefields within big, colossal sculptures on these heads of what it’s like going on in our heads right now,” Scuilla said. “… Everything feels very black-and-white right now, and what I try to do in my work, and what I find most interesting, is that gray area, that mystery, we’re all sort-of navigating through.”

Kurt Gartner

Dr. Kurt Gartner, professor of percussion, said it’s important people know his passion for teaching music “started with a great teacher.”

“Anything that I can claim as a success, I’m totally standing on the shoulders of some great, great teachers.”

Gartner, born and raised in Chicago, became a percussionist in the fifth grade.

“I like to say that music chose me as a profession,” he said.

However, it wasn’t until graduate school that Gartner discovered a love for Afro-Cuban music.

“Every which way I turn in the world of percussion, you’re looking at some whole new experience — new to you — a culture, or a new drum, or a new way of playing or way of thinking,” Gartner said. “So I am, like, the perpetual student, and I have to be comfortable with being a beginner at things, and that’s why I got into Cuban Music the way I did.”

Now, Gartner teaches the Latin Jazz Ensemble at Kansas State.

“Latin Jazz itself is the fusion of, in our case, Afro-Caribbean rhythms with jazz melody and harmony, and sometimes form,” he said.

In 2000, while teaching at Purdue University, Gartner took his first trip to Cuba after encouragement from professor and mentor Ruben Alvarez.

“I was just blown away with his enthusiasm as well as his knowledge, so I started driving from Purdue, from Indiana, up to Chicago to take all-day lessons with him,” Gartner said. “And I started putting a band together, a professional band also there in West Lafayette, and he was the one that encouraged me to go to Cuba the first time. He was actually my roommate the first trip there.”

Gartner completed his Doctor of Arts degree at the University of Northern Colorado in 2001 before coming to K-State.

“I was enjoying myself and doing well teaching at Purdue University, but at the time, anyway, there was no music major,” Gartner said. “So, I was working with a lot of really smart engineers and really smart folks in all sorts of other disciplines, but I really wanted to work with students and know that I was able to place them in the field as performers or teachers.”

Since his start at K-State, Gartner has returned to Cuba nearly every three years with Plaza Cuba, bringing students to immerse them in the history and culture of the music they’re studying through a 10-day intensive.

“As percussionists … we’re very hooked into the metronome,” he said. “For us, time becomes sort of rigid, like you’re punching a clock. You’re hitting a deadline. In Cuba, music is … a circle, and the most irrelevant question you can ask a Cuban drummer is, ‘Where’s one?’”

Gartner said allowing students to learn from musicians in Cuba teaches them intuitive rhythm.

“You just have to be moving along with it,” he said. “You just have to jump on at the right time.”

Gartner learns new things each time he travels to Cuba, bringing back firsthand knowledge to enrich his teaching at K-State.

“The experience of Cuba; amazing is such an understatement, or a cliche word,” he said. “The people are so gracious and so giving, and I think they also have a great appreciation that North Americans are taking the time to go there and study with them to get the real thing. So, I’m kind of cautious, in my teaching, not to branch far outside of the experiences that I’ve gained from my studies in Cuba, which is why I keep going back.”

One particular experience Gartner recounts involves a Latin Jazz Ensemble student who brought his trumpet along on the trip.

“He took his trumpet with us every night and sat in and played, and he was hanging with the Cubans,” Gartner said. “They let him up and let him onto the stage to play, but he was holding his own, and that’s super exciting. It’s like, the longer I’m in this, the more I’m there vicariously enjoying the experience that my students are having.”

After the COVID-19 pandemic, Gartner was only able to take three to six students per Cuba trip. However, he said every student in the Latin Jazz Ensemble understands the importance.

“One time when we were going to do the trip, the Latin Jazz Ensemble was playing, like at the Manhattan Arts Center, for example,” Gartner said. “They would get some funding from that, some pay for that, and maybe four of the members of a 12-piece band were going to Cuba, but all the band decided to direct all the funding from all those outside gigs that we played to the people that were going.”

Through teaching Latin Jazz, Gartner gives students an entry point to new styles and techniques.

“We have different types of tunes, arrangements and styles that meet the students where they live,” he said. “They might come in with a big jazz background and they can play over standard jazz tunes already, or maybe they’ve never improvised at all, but we have an open door for all of those situations.”